Back in 2011, when I started this Fantasy Reading List, I knew I would read all the books in The Dark Tower series by Stephen King, because I had always intended to read the series, and never had. When King first wrote The Gunslinger in 1982, he did not know where the story would take him or his readers, or if he would even ever finish it in his lifetime.

Fast forward to now, 2015: The Dark Tower has eight books, a short story, countless allusions in his other novels, Marvel comic books, books and dictionaries about the books, a massive website, fandoms, an online gaming world, conventions, and this very month, yet another announcement that this will be made into a movie, and possibly even an animated series.

The world has moved on. Bring it on.

I wanted to read the 1982 original novel, not the 2003 revision -- and fortunately my friend Taryn had the original we had both read many years ago, still in her library. This is such a creepy, soulful story. Stephen King took Browning's epic poem "Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came" as his muse, but this story brought to me the distinct feeling of another very mystical poem, perhaps a twisted version of such -- Dylan Thomas's "Fern Hill."

Roland, the gunslinger, the last of his kind, a lord of light (Zelazny, anyone? Anyone?), chases across a freakish wasteland of sacrifice to catch the man who black who can point him to The Dark Tower, his fate. Here, sex is a coin of offering for needed knowledge and the murdering of innocence and innocents is paid upon acquiring it. It is a world that twangs with wrongness, the kind of which can only be evoked by the dancing poetry of words, a Dylan-Thomas-ic clashing of images. So much of this really got me; I will put down some of my favorite passages.

"There were fields and rivers and mists in the morning. But that's only pretty. My mother used to say that ... and that the only real beauty is order and love and light."

"And there had been the falcon, of course. The falcon was named David, after the legend of the boy with the sling. David, he was quite sure knew nothing but the need for murder, rending and terror. Like the gunslinger himself. David was no dilettante; he played the center of the court."

"The center had frayed like a rag rug that had been washed and walked on and shaken and hung and dried. The lines and nets of mesh which held the last jewel at the breast of the world were unraveling. Things were not holding together. The earth drew in its breath in the summer of the coming eclipse."

The poet disappears and the horror writer returns for the first third of this book. Gunslinger Roland traverses an alien beach to locate three companions for his odyssey: an amicable heroin addict, a fascinating and brilliant multiple-personality heiress, and to Roland’s horror, a monster who kills for perverted joy rather than a damning quest. This first part is overwritten, with too many words by far, mostly because of the repeating of each scene from every character’s point of view, which annoyed me. Also, I fear how well the 80’s jargon in this first section will fare with time. (It made sense to me, because I was in my twenties back then, but anyone born a decade later might be completely lost.) However, this #1 best seller certainly did its job back in 1986.

Still the entire book was a quick and engrossing read, and I especially enjoyed the poignant relationships King creates between these characters. (Another plus is that he actually likes women and children, and his books are not elongated misogynistic rants.) And as Roland spends more time in own world, the poetry begins to seep back. Part of this is that King has to write more cleverly to convey such an alien landscape – and the words and phrasings of poetry seem the best tools for this particular job. I think that another part is that Roland is King: and like Roland Stephen King is himself a deeply romantic and poetic, though undeniably dark, soul.

Some of my favorite parts:

A Mobster building a tower of playing cards: “…a red and black configuration of paper diamonds standing in defiance of a world spinning through a universe of incoherent motions and forces; a tower that seemed to ‘Cimi’s amazed eyes to be a ringing denial of all the unfair paradoxes of life. If he had known how, he would have said: I looked at what he built, and to me it explained the stars.”

"Fault always lies in the same place, my fine babies: with him weak enough to lay blame.”

“The gunslinger felt a dull species of shame…”

"If you have already given up your heart for the Tower, Roland, you have already lost. A heartless creature is a beast. To be a beast is bearable, although the man who has become one will surely pay hell’s price in the end, but what if you should gain your object? What if you should, heartless, actually storm the Dark Tower and win it? If there is naught but darkness in your heart, what could you do but degenerate from beast to monster? To gain one’s object as a beast would be bitterly comic like giving a magnifying glass to an elephaunt. But to gain one’s object as a monster… To pay hell is one thing. But do you want to own it?”

The Waste Lands

The third book of the Dark Tower is rife thematically, a story of increasing insanity, which comes in waves: a gigantic bear “guardian,” Roland himself, the boy Jake, the residents of the city of Lud, the ruined mechanical heart of Lud itself, and of course, the train Roland’s little party must board at very end of the story. Informed by so many different books and poems – especially T.S. Eliot’s titular poem, so dear to my heart – this book is remarkably devoid of writing that rises above Stephen King’s sturdy and well-known film-like visuals. It would be easy to say he was just churning out another book, but I am wondering if this was also not because this is a story with a lot more action in it, a lot more scenery-changes, too, and perhaps the prose is at some level pared down to service that. I really like the story of The Waste Lands, and the development and evolution of Roland, but I missed the poetry.

My favorite member of Roland’s band is Oy, a billy-bumbler that mimics words it hears. It is a silk-furred animal described as a cross between a woodchuck and a raccoon, and in my mind, had the golden-eyed visage of an aye-aye. I can say I liked Oy too much, especially when I realized “Oh, no! This is a Stephen King novel! Something awful is going to happen to little Oy!” It was a moment.

This is the last book I read in the 80s of this series, and I remember really loving it. And I loved it again reading it this time. It is my very favorite so far: Roland’s coming of age story, a love story, the “Glass” part of the title. It is tender, bittersweet– Roland at fourteen years of age, and his two best friends Cuthbert and Alain, go into hiding in a rural town and discover a nefarious plot, love, and of course, the call of the dark tower. Alain seems poorly developed, but everything else about this tale is stellar. This story has two bookends. The first is the finished cliffhanger of the previous book with Blane the Pain Train – which I felt was unsatisfactory, as if the author had grown bored with it and just wanted it to be over, and the much more interesting visit to a very twisted version of Oz by a much older Roland and his new companions, Eddie, Susannah, Jack, and Oy.

This Oz section is the “Wizard” part of the quest, and only now I realized what Stephen King had probably known when he had put it in. The Wizard of Oz is a Hero’s journey of the highest order, as high as Ulysses’ Odyssey, as high as Childe Roland’s quest for the Dark Tower – and that all of the goals for these great adventures are the same thing: to find your way home.

As I pondered this story while on vacation in Ireland, England, and Wales – the lands of myth – I had two wonderful epiphanies. The only way Stephen King got this 700-page story done, as well as the other seven books he wrote for this series, and the over fifty books he’s written during his life, was to write like a fiend. To finish books, you need to write write write write write… learning about writing, developing stories is not writing. To write a book, you need to sit down with pen (or computer) and put the long hours in. My other epiphany was this: I know how to write a selling story. It’s not a mystery to me. So I need to do it.

Here are some of the greatest parts of Wizard and Glass:

“Roland was far from the relentless creature he would eventually become, but the seeds of that relentless were there – small, stony things that would, in their time, grow into trees with deep roots… and bitter fruit. Now one of these seeds cracked open and sent up its first sharp blade.”

“But his eyes never left hers, and in them she saw some of Roland’s truth: the deep romance of his nature, buried like a fabulous streak of alien metal in the granite of his practicality.”

“So do we pass the ghosts that haunt us later in our lives: they sit undramatically by the roadside like poor beggars, and we see them only from the corners of our eyes, if we see them at all. The idea that they have been waiting for us rarely if ever crosses ou minds. Yet they do wait, and when we have passed they gather up their bundles of memory and fall in behind, treading in our footsteps and catching up, little by little.”

See? Beautiful. Also, Oy makes it to the end of this story, thank goodness.

A Wind Through the Keyhole

Time is a keyhole, he thought as he looked up at the stars. Yes. I think it is. We sometimes bend and peer through it. And the wind we feel on our cheeks when we do – the wind that blows through the keyhole – is the breath of all living creatures.

This book came out in 2011, but King considers it 4.5 in the Dark Tower Series, so I read it in after Wizard and Glass. It follows WaG’s form of story-within-story, but here, there are two nestled stories – two sets of bookends, rather than one. (I will be very interested to see if and how this thematic device plays out in future books.) The outermost shell story is that of Roland as he travels with his companions toward the Dark Tower, and serves only as framework for the other two stories.

The next story in is another story about Roland’s youth, which is a setting that I find deeply enchanting, even though the story is uneven; this is a story being told in first-person by old Roland from the point of view of young Roland, and I think that makes for an odd tone in places.

The heart of the book is The Wind Through the Keyhole, a fable young Roland shares with a frightened child. This central tale is even more uneven. The lows were that the story telegraphed its plot points so loudly it hurt, but I think the highs counteracted those lows, because it has the most thoughtful images and lines of entire novel:

“…for I know what he is – pestilence with a heartbeat.”

“The tyger saw him and came padding around the hole in the middle to stand by the door of the cage. It lowered its great head and stared at him with its lambent eyes. The wind rippled its thick coat, making the stripes waver and seem to change in places.”

“Its purpose had been served, and all the magic had gone out of it.”

I guess I was wondering at the purpose of this book. Its theme is certainly “forgiveness,” following the themes of sacrifice, insanity, and love; and it brings out its Arthurian Matter in a lovely way; but is it really needed for the tale of The Dark Tower? Or was it written for the love of Roland’s old world alone? For the love of Roland by its author? I will find out as I read more of the books. But I think for those who love that world (and I do), that is enough.

And Oy is still alive.

Wolves of the Calla

This book is seven hundred pages, but it would have been so much better if it had been three hundred pages, instead. So much of it felt like filler to me – the back story of Father Callahan (and reading this at the same time I was reading a Thomas Merton collection created a bizarre amalgam in my head) who comes from a different Stephen King novel (Salem’s Lot), the empty lot drama back in Calla New York, and the Susannah-Mia-demonic-baby sub-story. Moreover, the big surprise of the true origin of the child-destroying Wolves was not only not that surprising, but was withheld information – the characters knew it, but the reader did not…for about three hundred pages. Story Jesus is not pleased.

All together, this was more than a little annoying. It was a lot annoying. It was all I could do to keep from skimming the last two hundred pages. If I were giving this book to a friend to read, I would cross out the superfluous sections so that they could enjoy the real gems in this story.

It felt like it caved into Stephen King’s weaknesses, and so much so, it really overwhelmed the central and good story of a western outpost seeking help from the Gunslingers of Eld, and more really touching character-building on the Gunslinger himself, Roland Deschaine. It didn’t help that the ending borrowed far too liberally from Star Wars, Marvel Comics, Stephen King’s Other Book, and even Harry Potter.

No.

Oy’s alive, and may stay that way. But I’m worried about these last two books.

Song of Susannah

I was nervous, starting this book. I didn’t like Wolves. And Susannah is the least favorite of my characters in this story (who are, by the way, Oy, Roland, Jake, and Eddie). I hadn’t liked her old personality (Detta) at all, and I wasn’t won over by her newest and pregnant psychic visitor, Mia. Worse, I had read the complaints from other readers about how Stephen King makes himself a character in this story, and I was dreading that with all my heart.

But wait. This story is readable. It is interesting. There is an ease in the writing that invited me in, made me enjoy the characters as they desperately try to find Susannah, who has been possessed by the pregnant Mia and taken to 1999 New York. Mia herself, who is a true villain, was very interesting indeed. Her character could have been developed even more, I thought. Oy was almost – oh, my heart nearly stopped – run over by a taxi.

Remember: Oy is my favorite character.

The priest Callahan is still a completely unneeded character, as is King himself, but it is not as egregious as I thought it would be: forgive me, but as a writer, I enjoyed hearing his own opinions on his writing process. After all, most writers, to one degree or another, write themselves into their own stories. Mr. King was just being more honest than most. Still: not needed.

There were many moments in this book that I thought were almost stunning, and would have devastated readers if the writing had been handled a little more carefully. They were great, but they could have been greater. It’s a reminder to look for those moments in my own writing.

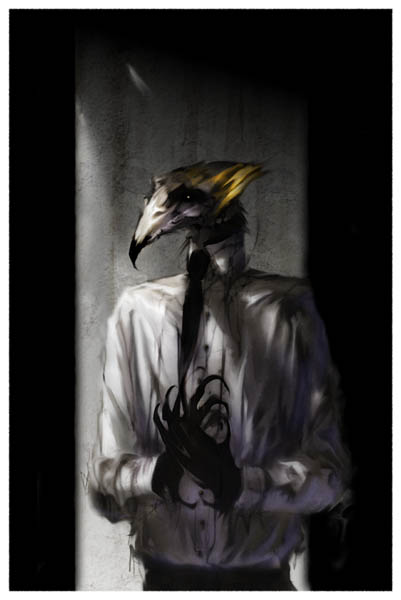

Also, I haven’t mentioned it before, but most of these books have been filled with color artwork. As far as I am concerned, all books should have illustrations. (Also, dodos and pterodactyls, but I digress.) But the illustrations for this Dark Tower tale are the absolute best – creepy, moody, haunting, evocative. The artist is named Darrel Anderson. The best one was Jev, the Hawkman.

I wished he’d drawn a picture of Oy.

“Once upon a time when everyone lived in the deep dark forest and nobody lived anywhere else, a dragon came to rampage.”

"Roland had taught him that self-deception was nothing but pride in disguise…”

“He used to tell me that never’s the word God listens for when he needs a laugh.”

“But my teacher, Vannay, used to say there’s just one rule with no exceptions: before victory comes temptation. And the greater the victory to win, the greater the temptation.”

“The Dark Tower is existence,” Roland said, “and I have sacrificed many friends to reach it over the years, including a boy who called me father. I have sacrificed my own soul in the bargain, lady-sai, so turn thy impudent glass another way. May you do it soon and do it well, I beg.”

“Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came” by Robert Browning was a poem I learned about from one of my two dearest friends, Taryn, who was an English major in college. When she was given this poem in school, she shared with me her utter amazement of the story: a knight spends his entire life going to fight the greatest evil in the world, and when he finally reaches it, this Dark Tower, it is so evil he cannot face it. He can do aught than announce his arrival. The great import of this really struck her, and of course, me.

Does Stephen King share the same interpretation Taryn gave me so long ago? In a way. (There are almost as many interpretations of this poem as there are words in all these books Mr. King wrote. The Tarynesque one is the nearest and dearest to my heart, though I would like to delve into these new-found interpretations, later.)

But first, my own interpretation of this Roland and this Dark Tower.

In the preceding books, as well as this last one, I felt definite themes coming forward. (King actually developed his own sense of themes for these books that he shared half-way through them, but mine work better for me. So there. Interpretation again.) They are: sacrifice, loss, insanity, love, forgiveness, aging, motherhood, and in this last book, which is actually two, fatherhood and fate (Ka, Life and Death, or what have you).

At over 1,000 pages long, this last tale is really two separate books: first, the story of finally saving the damaged beams that hold the tower (and all of reality) in place, and second, Roland’s final arrival at his nemesis and greatest love, the Dark Tower.

The first book resolves many story lines, including the ones that vexed me most, and takes us to a fascinating place: Blue Heaven, the home/jail of the people who are trying to destroy the last beams that hold up the Dark Tower. I was thrilled by the new world and culture presented – the animal-headed taheen, the jealous low men, the stolen “humes.” Love and violence intermingle in the only way they can, the result being heartbreak and soul-searching. The tragedy comes to its apex in Roland, who realizes how much he loves everyone – he begins to address men and women both as “dear” and bestows sincere kisses on those he loves: his open heart is the most touching and redeeming part of this book.

Stephen King himself is the flaw because he actually is in the story. As I was reading it, I was trying to figure out why it bothered me so much. I had already noted in Ender’s Game becomes better when the Orson Scott Card gets out of his own way and lets the Story come through – and in The Dark Tower Stephen King is physically there to get in the way of the Story! Authors, I think, are not the Story – they are but the vessel, though they get confused about that, all of them, all of us. I just read an interview with k.d. lang this week, who reiterated this: “…I think real creativity comes from getting the heck out of the way.” (Or to quote King from this very story: “To peek into Gan’s (God’s) navel does not make one Gan though many creative people seem to think so.”)

The other thing that bothers me is Stephen King’s tying the back-tying The Dark Tower into all his other stories, past and future works, all. It’s not needed and interferes with the Story itself. Again, this is not unforgivable: all writers write the same story over and over again. I’ve seen it in so many authors and in myself, and because King has written so much, I know the story he writes. (It is this: We want there to be happy endings, but there are not.) He actually states it in this book: There is no such thing as a happy ending. I never met one equal to “Once Upon a Time.” Endings are heartless.

Lastly, in the story and in the afterward, Stephen King tries to explain what he has done (putting himself in the story, and what actually happens in the story), and this conflicts directly with a writing lesson from high school I value: if you have to apologize for or explain your work, well, don’t do it. Let your work stand for itself. Make your work stand for itself.

The second book is where Roland starts his final approach to the Dark Tower – and Stephen King reminds us (a) he is a horror writer, and (b) there are far worse things than dying, which he inflicts them on the characters we’ve grown to love. I cannot forgive the pain Oy suffers here. I just can’t.

But in this darkness and sadness, the poetry of this story also comes to the surface again, and beautifully. Roland’s High Speech – a language to describe soul and heart – sounds so real, as do the souls and hearts of all these characters. The vernacular everyone uses – which sounded funky when it was adopted in Wolves of the Calla – creates a rhythm that drives the Story to its end… and made me realize the real lesson for writers in these books: Story is Rhythm. Each story has its own beat, that a reader recognizes as what reality feels like. A talented author such as King uses rhythm to create a resonate world. Anything that breaks rhythm breaks Story. No writer does it perfectly, and King acknowledges this, too, in the afterward.

So, after all this, you might ask, is this series worth reading? My answer right now is this:

It is what it is: like all authors, Stephen King sometimes gets in the way of his own story, and he does so equally as spectacularly as when he lets the rhythms of Story rule. It’s what is offered, like fate itself. The characters and their love for one another won me over without any reservations: I cried real tears for Oy, which I rarely do for anything in this world. So if something wins you over in this long tale and makes it real to you, it is worth it. If not, not.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed